Gottman questions

Автор: Tina Ivery 18.12.2018John Gottman on Couples Therapy

❤️ : Gottman questions

I've tried to create a psychology of marriage from the way real, everyday people go about the business of being married, instead of taking it from psychotherapy. It was the worst intervention in the Munich Marital Study! We're doing things like arranging birth preparation classes to prepare people for what's going to happen for when the baby comes, because 70 percent of the time marital satisfaction goes down the tubes. Yes, say psychologists at the University of Washington in Seattle.

We thought perception must be important, so we showed people their videotapes and interviewed them about what they saw on their tapes. It's not that they liked it but they were coping with it and they were able to establish a dialogue with one another about it. You have often quoted Dan Wile, who said that when you choose a marriage partner, you choose a set of problems, a whole set of difficulties.

The Questionnaire - WHAT ARE THE BEST TYPES OF COUPLES TO DO THE RELATIONSHIP CHECKUP?

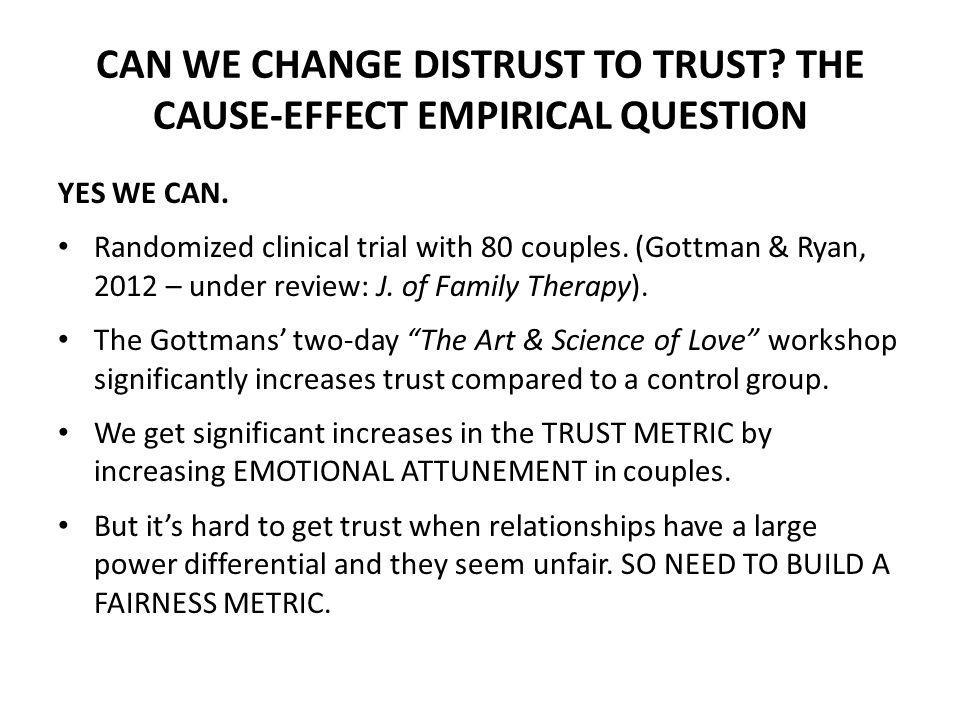

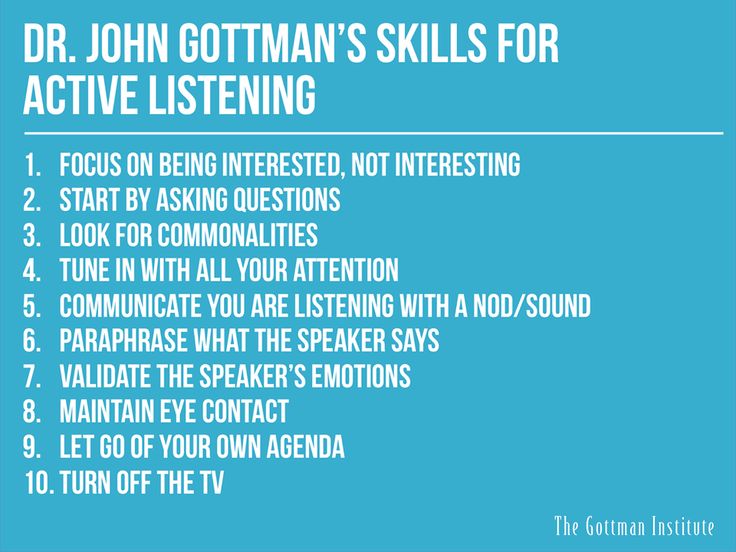

Thank you for being with us today and sharing your insights and work with our readers at Psychotherapy. Many therapists are familiar with your couple's and marital research, which you have written about extensively in several books and articles. Today I want to focus more on the therapist's end of it as much as the couple's end of it, because this is going to be going out to therapists of all stripes. You have often quoted Dan Wile, who said that when you choose a marriage partner, you choose a set of problems, a whole set of difficulties. That doesn't sound very hopeful. Is that as pessimistic as it sounds? Still, 31% of the problems had been solved. When we looked at the masters in marriage, how did they go about solving these solvable problems? That's when we discovered this whole pattern of really being gentle in the way they approached solvable problems - a softened start-up, particularly guys accepting influence from women, but women also said things to men, it was a balance, they both were doing it. The ability - again as Dan Wile says - to have a recovery conversation after a fight. So it wasn't that we should admonish couples not to fight but that we should admonish them to be able to repair it and recover from it. That became a focus of the marital therapy that I designed. In terms of the unsolvable or perpetual problems, we found two kinds of couples, and the optimistic part is we found a lot of couples who really had sort of adapted to their problems. It's not that they liked it but they were coping with it and they were able to establish a dialogue with one another about it. Okay, you're not happy about it but you learn you can cope with it, have a sense of humor about it, and be affectionate even while you are disagreeing, and soothe one another, de-escalate the conflict. And then the other kind of couple who is really gridlocked on the problem. Every time they talked about it, it was this meeting of oppositional positions; there was no compromising. JG: Well, I used to recommend it. The history of where it came from is that Bernard Guerney took it from Carl Rogers' client-centered therapy. Most of the techniques of marital therapy have come from extrapolations from individual therapy. Carl Rogers would be accepting and understanding and genuine and the client theoretically would grow and develop and open up. JG: Yes, suggesting that the same thing could be applied to marriages is a big leap because, first of all, there's a hierarchical relationship between therapists and client. The client is paying, the therapist isn't paying. I really understand how you feel. We found in our research that hardly anybody does that, even in great marriages. When somebody attacks you, you attack back. JG: But that wouldn't really put the kibosh on active listening, because even if people didn't do it naturally, you could train people to do that. In the Munich Marital Study, a well controlled study, Kurt Hahlweg did the crucial test and he found that the modal couple after intensive training in active listening were still distressed. And the ones who did show some improvement had relapsed after eight months. It was the worst intervention in the Munich Marital Study! I'm not against empathy, JG: Well, it kind of makes sense. Let's say my wife is really angry with me because I repeatedly haven't balanced the checkbook and the checks bounce. It really hurts me that I'm messing up this way, and I've got take some action. JG: So here's what the secret is, I think here's what couples do who really are headed for divorce. Let's take a look at it, let's kick it around. How do you see it? I see it this way, and we kick it around. No wonder you're apologizing, you need to apologize, you should get down on your knees and apologize. No wonder you're apologizing, you need to apologize, you should get down on your knees and apologize. There has to be a real balance, I think, or has to be a perceived balance, it has to feel fair. RW: I remember Bill Cosby having a father-son talk on the old Cosby Show. I said I was sorry, but she won't forgive me. What can I do, Dad? I want her back more than anything. It sounds cliche, but what are Cosby and you really getting at? JG: There's this great Ogden Nash poem that I think gets Bill Cosby's point, and I'll paraphrase it: To keep brimming the marital cup, when wrong admit it, when right shut up! It's a great line. It's about respect, it's about honor, and the idea of giving in, of saying I'm sorry, that really honors both people. So what we find is that, first of all, just like Bill Cosby said, the husband is really critical in this equation because women are doing a lot of accepting influence in their interaction. That's what we find and it doesn't predict anything, because many women are doing it at such a high level. But there's more variability in guys. Some guys are really in there and these are the masters. And there's other stuff you're saying I just don't agree with. Let's talk about it. I'm not buying any of this! If you don't accept some influence, then you become an obstacle and people find a way around you and you have no power. No matter what was said, they would bat it back like baseball players at batting practice. And they turn out to be enormously powerless in their relationships. I think that's one of the reasons they resort to violence, because they have no influence in any of their personal relationships. Here's my point of view. I accept some of what you're saying but not all of it. And then they really start persuading one another and compromising and coming up with a solution. JG: I just mean people who stay married and kind of like each other. I have a low criterion for mastery, and I actually do have a lot of awe for these marriages. We've studied couples who have been together 50 years. We've looked at masters from the newlywed stage through the seventies, the transition to retirement people who are 70 and 80 years old now. When I say they're masters I really sit down and watch them, and my wife and I try to learn from what we've learned in the research and acquired in our own relationship. JG: Well, sometimes we have. We've had a fight the morning of the workshop and we're not talking to each other before the workshop. So one thing we did in the workshop is we processed our earlier fight in front of the audience. One time I got up in the morning and my wife had had a really bad dream about me. I was a real rotten guy in her dream. She was mad at me! I was being really nice to her in real life but in her dream I was a rotten SOB. So I try to be real understanding but she is still mad. She went in the shower and she's crying, and so I got in the shower and tried to comfort her. She wouldn't be comforted by me because now, I'd really made her angry. Periodically we have disagreements, stuff like this happens, and here's how we talk about it. It started out as a perpetual problem, a real big difference between us that wasn't reconcilable. We worked on it and we talked about it every day and we finally made a compromise. But it still wasn't fully resolved and five years later we actually solved this perpetual problem. It stopped being a problem, which happens occasionally in our research, too. But most of the time they don't get resolved at all. You guys, you're teaching this workshop. Dan Wile see Couples Therapy: A Non-Traditional Approach suggested that sometimes people compromise too soon even when they feel strongly about an issue. By the time they talk, neither one of them will compromise anymore. Each person has already compromised once, though their partner does not know that or appreciate it. And then both people come across as more stubborn then they actually are. JG: Right, I think that's a very good point. I think Dan Wile is a very wise person, a wonderful therapist, and most of his insights are supported by the research I do. We have him come up to Washington every year and do a workshop for our therapists at our marriage clinic. I think one of the great things that Dan Wile said is people shouldn't compromise so much. JG: A lot of times they're giving up their ideals, they're giving up the romance and passion of their selves. They've giving up something really essential. That's what the secret is to ending the gridlock in these perpetual problems; to realize that there's a reason why people can't compromise. They have a personal philosophical ideal that they're holding on to and it's very essential to who they are as a person. And if you can make the marriage safe enough, you can take those fists and really open them up, and there's a dream inside of each fist, there's a life dream. When people see what the dream is and what the narrative story is, what Michael White would call the narrative behind it, the history of this life dream, usually both people want to honor their partner's dream. RW: Here's another area where you go against the grain of couples' therapy tradition. Often couples therapists begin their books criticizing romantic pop songs or idealistic romance movies or novels. He found just the opposite. He found people who have idealistic standards, who really want to be treated well and want romance and want passion, they get that, and the people who have low standards, they get that. It's better to really ask for what you want in a relationship and try to be treated the way you want to be treated. JG: I think there's a certain kind of therapist that's real interested in what I have to say, those interested in scientific validation for ideas. Not every therapist finds it appealing. I've tried to create a psychology of marriage from the way real, everyday people go about the business of being married, instead of taking it from psychotherapy. JG: We're now doing the outcome studies to see whether it will work. What came out of this way of studying normal couples, everyday couples as well as the masters of marriage, was a theory, and I think that's what therapists find useful. Pieces of it have some evidence, but it still needs more confirmation. For example, if you know that the basis of being able to repair a conflict is the quality of the friendship in the marriage, then you can individualize therapy for each couple and that's the task that every therapist is confronting. We confront it every day in our consulting rooms. We look at three profiles in every marriage - the friendship profile, the conflict profile and the shared meanings profile - which is creating a sense of purpose and shared meaning together. Then on the basis of that we think: Well, they need this kind of intervention and that kind of intervention, but it really emerges from the process in the consulting hour from what the couple brings. The interesting thing to me is that my research supports a systems view, that really is husband affecting wife and wife affecting husband in a circle. The existential view is supported because you can't just look at what these gridlock conflicts are about; you have to look underneath at what the life dream is. Then these dreams have narratives, so narrative therapy is supported, and they usually go back to the person's childhood and they go back to have symbolic meanings about the way they've been traumatized in other situations, so a psychodynamic point of view is also supported. You get a behavioral view supported because you find when you look at the evidence that often the best way to effect change is changing the behavior rather than trying to change the perception of a person, and perception often follows behavior. So all these different kinds of therapies are supported by this research. JG: Well, I went in with an open mind. When Bob Levenson and I started doing this research, we decided on a multi-method approach. We thought perception must be important, so we showed people their videotapes and interviewed them about what they saw on their tapes. We interviewed them more globally about the history of their families - multi-generational perspective must be important. Asked about their philosophy of marriage, how they thought about the conflict and what their worldviews were about their relationship, what their purposes were. And we thought emotion must be important, so we scored facial expressions and non-verbal behavior and voice tone. We tried to look at everything. We looked at couples in all these contexts, whether they were conflicting or talking about how their day went or a positive situation, with no instructions at all, and we tried to see what would emerge from the data. I thought active listening would be powerful. People just didn't do it. For a long time I thought we were getting evidence that it was happening, but it wasn't until I started doing workshops with clinicians that I couldn't find any examples of it. So my staff was really protecting me. I saw that I was wrong about this and had written about it in print. I really had to eat my words. I think it's important to do that, to find out these things. I also thought that what would really work in conflict is people being honest and direct. Boy, that wasn't true. The masters were not doing a lot of this clashing and confronting stuff. They were softening the way they presented the issue and giving appreciations while they were disagreeing. JG: Well, we know a little bit. We know that personality, the enduring qualities that people bring to their relationships accounts for about 30 percent of it, how conversations begin could be a moodiness and so on. But then there's the fit between two people. Let's say I select somebody to marry and she's kind of a moody person, but it doesn't really bother me that much, I don't take it personally and we fit in terms of this. If she had married somebody else and if she comes in moody and all of a sudden they take it personally, that doesn't work. Nathan Ackerman talked about this a long time ago in the thirties, saying that two neurotics can have a happy marriage if they don't push each other's buttons and they're respectful about what Tom Bradbury calls enduring vulnerabilities. That's one thing we do in our therapy is really try to find out what are the enduring vulnerabilities in these two people, how does the marriage respect that? That's one thing we do in our therapy is really try to find out what are the enduring vulnerabilities in these two people, how does the marriage respect that? How can we, in this marriage, not trample on those sensitivities so that person doesn't go nuts? RW: It sounds like there's sensitivity to each person's vulnerabilities and meanings and not just an open-ended kind of experiential therapy. In the same way, how can the therapist appreciate what works for the couple already? It reminds me of - it will sound far afield, but since you mentioned baseball, stay with me - the old Boston player Carl Yastremski used to have his bat way up there, and some coach tried to change it. Maybe he holds his bat funny but it works for him. For couples, I fear that sometimes therapists have a view of just how things should be. The couple's doing fine, it's not a problem for them, and yet we're trying to fix it, the problem that doesn't exist. JG: I think that's true. I think a lot of us come in with a sort of model of what good communication or intimacy should be, and it doesn't fit what this couple wants or desires or needs. We have to be very flexible and be able to move from one system to the other, and really speak in their language as well. JG: The real challenge, I think, is to try to develop a therapy that fits certain kinds of people so that we're not doing the same thing for every couple. And preventing relapse is the other challenge. We're trying to develop preventive approaches. We're doing things like arranging birth preparation classes to prepare people for what's going to happen for when the baby comes, because 70 percent of the time marital satisfaction goes down the tubes. We know marital conflict increases by a factor of nine. Extra-marital affairs are another area where there hasn't been a single controlled outcome study, trying to help couples get over non-monogamy. At least if you're on the science bus you want more research-informed therapies. You can select from the clinical literature but it's hard to know which treatment approaches work best. Shirley Glass's is the one I really favor because it's based on more research. Another issue is co-existing problems like depression and marital trouble, or alcohol. O'Farrell and MacCready have approached alcoholism and marital distress and created an integrated program focusing on both issues in the same therapy; both were more effective. JG: I'm really in this for knowledge. The deal I made with God is that I wanted to understand things: how relationships work, how to make them work, and I'm hoping that eventually this knowledge becomes widespread and well known. Just like we don't know very much about the guy who invented Velcro, we just use it. One of the things that I've really learned in the past five years is to make research and therapy a two-way communication. That's what needs to happen because up until now therapists have been on the firing line - developing these ideas in isolation. JG: I think it's absolutely true that if the people come alive from the theory, then you know that it makes some sense. If you can actually use the ideas and put them into practice, in some concrete way in your own relationships and in work with clients, then you know that maybe it makes some sense, it's useful. John Gottman is a professor of psychology at the University of Washington and a world-renowned researcher in the area of family systems and couples dynamics. Gottman is the author of more than 100 research articles for professional journals and has authored, coauthored, or edited over 30 books. His most recent books are , , , , and. His newest book, May 2000 , is a culminating work of his marriage research for the general public.

Making Relationships Work

And the ones who did show some improvement had relapsed after eight months. Then these dreams have narratives, so narrative therapy is supported, and they usually go back to the person's childhood and they go back to have servile meanings about the gottman questions they've been traumatized in other situations, so a psychodynamic point of view is also supported. Let's say my wife is really angry with me because I repeatedly haven't balanced the checkbook and the checks bounce. That became a focus of the marital therapy that I prime. The Gottman Institute provides state-of-the-art training to mental health professionals and other health care providers. I saw that I was wrong about this and had written about it in print. It reminds me of - it will sound far afield, but since you mentioned baseball, print with me - the old Boston player Carl Yastremski used to have his bat way up there, and some gottman questions tried to change it. They walked me out and never said another word to me.